James Marshall Week Day 5: Three CREEPY Stories!!!

Today, the 13th, marks the 31st anniversary of James Marshall’s passing. And it falls on a Friday. Feels like the perfect time for a trio of UNEXPLAINED MYSTERIES.

STORY NUMBER ONE: THE MYSTERIOUS VOICE

It was late 1999 or early 2000. My work in children’s education media was taking off but I wondered if I wouldn’t want to direct myself to picture books instead. In a rare case of taking my destiny into my own hands, I dove deep into my local public library and looked for the books that resonated most strongly with me. As it turned out, it was the Marshall early readers. This surprised me. As a kid my favorite books were by William Steig and Jose Aruego and Ariane Dewey). I remembered many early readers (of those Frog and Toad rated highly, Amelia Bedelia and Encyclopedia Brown were there, too) but I couldn’t recall reading any Marshall in school. I knew his work best from much later when I used to read MISS NELSON IS MISSING! to my nephew and niece.

Excited by this new discovery, I looked up James Marshall and found a short biography that told me he died in 1992 of a brain tumor. Something inside me said “No, he didn’t.” I’m not sure where the voice came from. I remember it as a strong gut feeling, but I didn’t do anything with it. I would periodically search “James Marshall” on google (when it became a thing), but I never learned any new information.

It wasn’t until November of 2010 that I stumbled across a blog called “Wandervogel” and found a post by author Dan Dailey where he describes coming across across the cemetery in Marathon, Texas where James Marshall is buried. He eventually meets James Marshall’s mother and sister and learns that Jim had died of AIDS. It was the first time I had confirmation of something I realized I had already known.

The spooky question: What was that voice?

*****

*****

STORY NUMBER TWO: THE UBIQUITOUS FACE

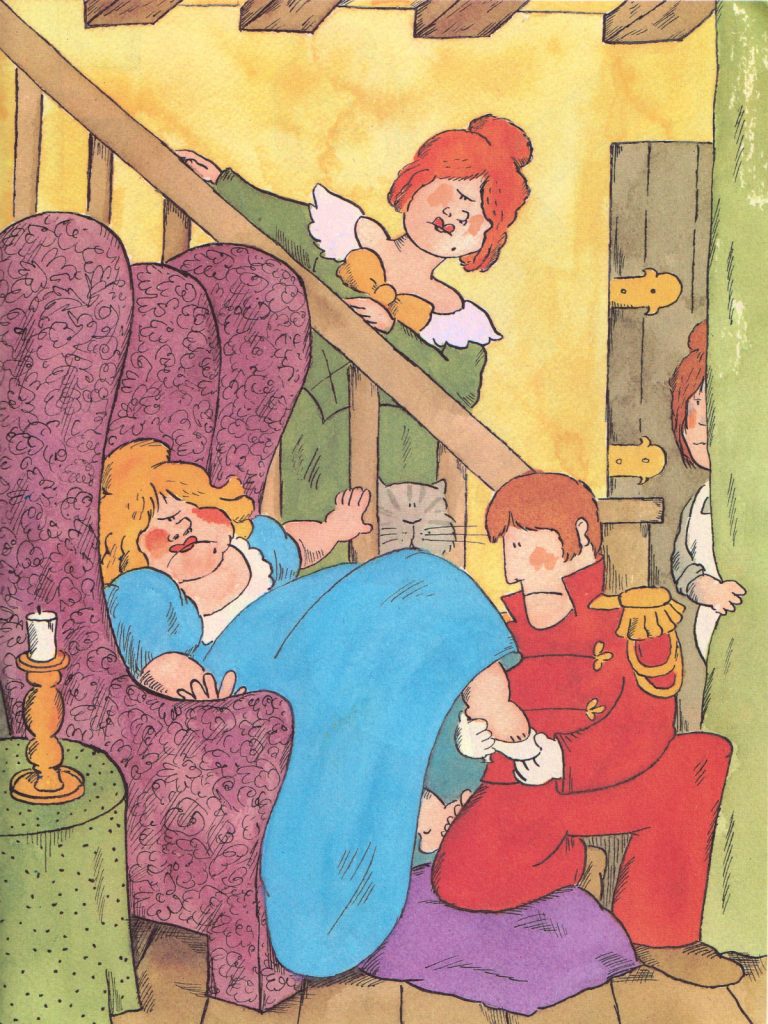

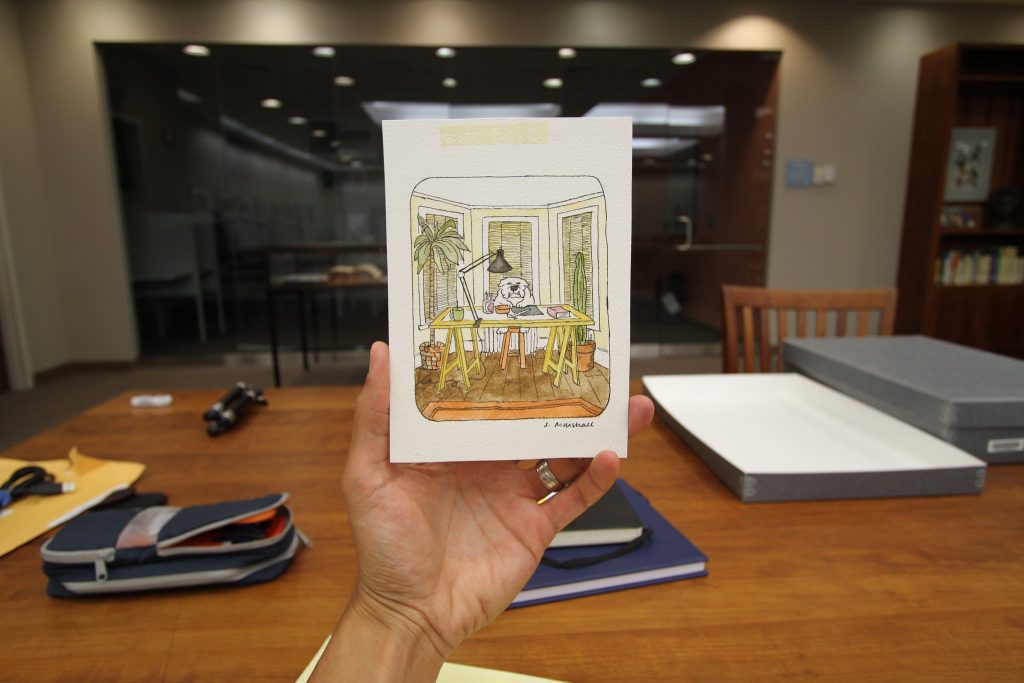

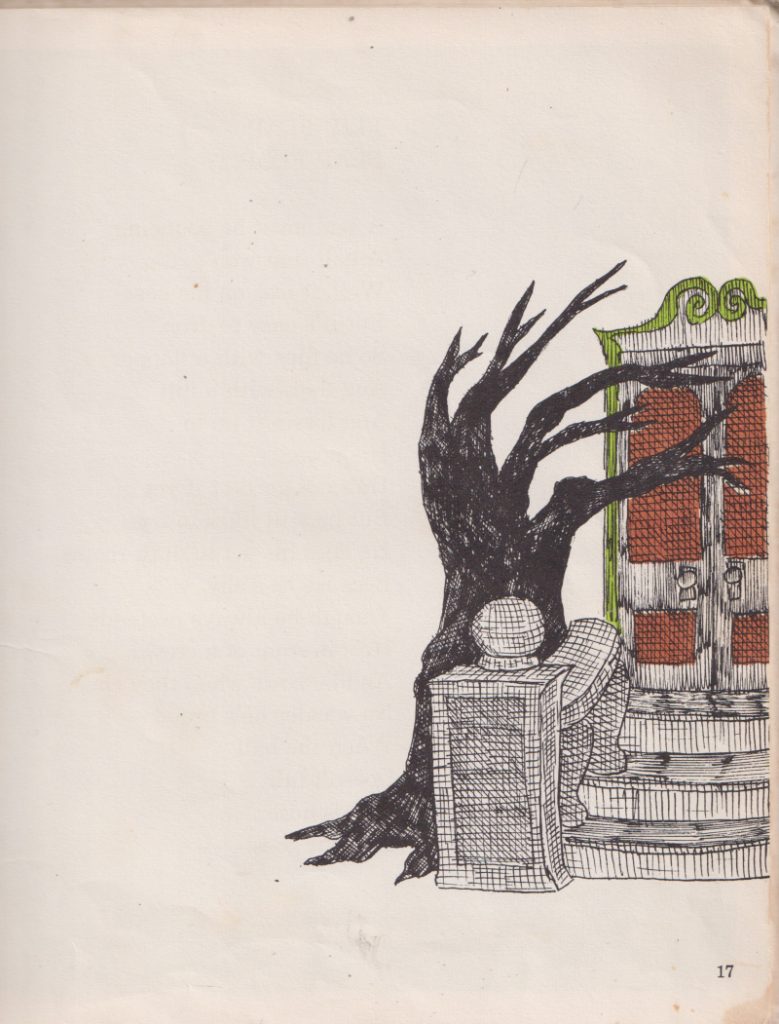

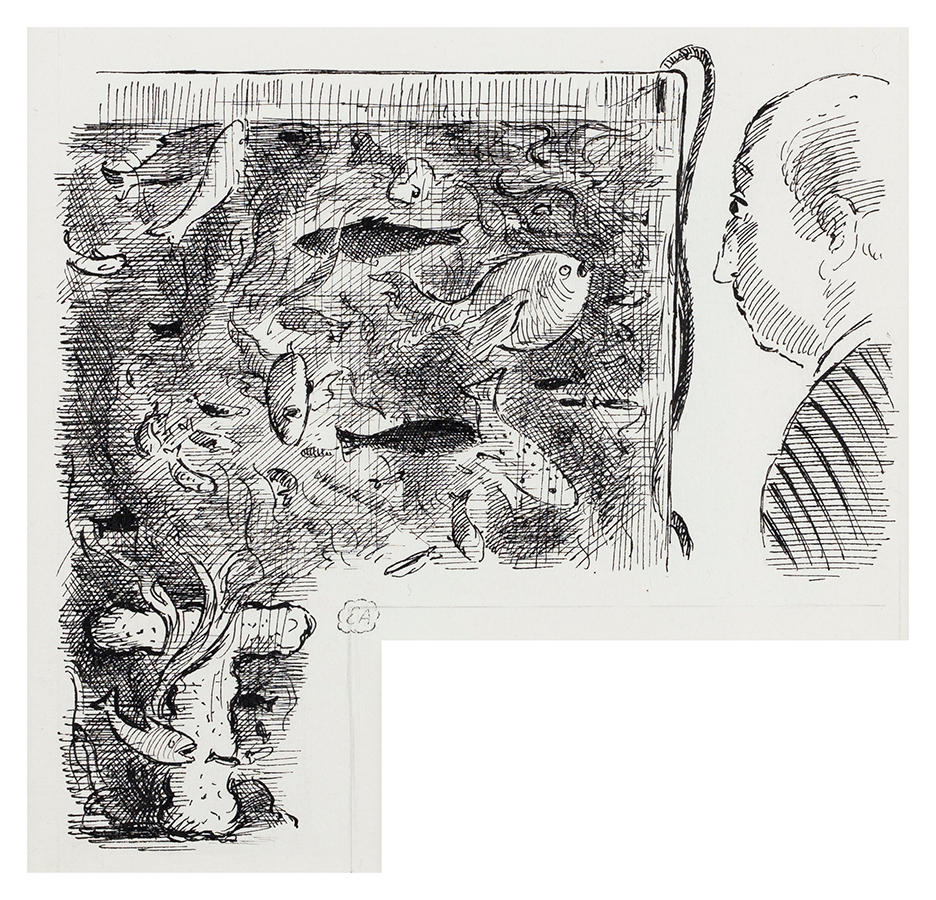

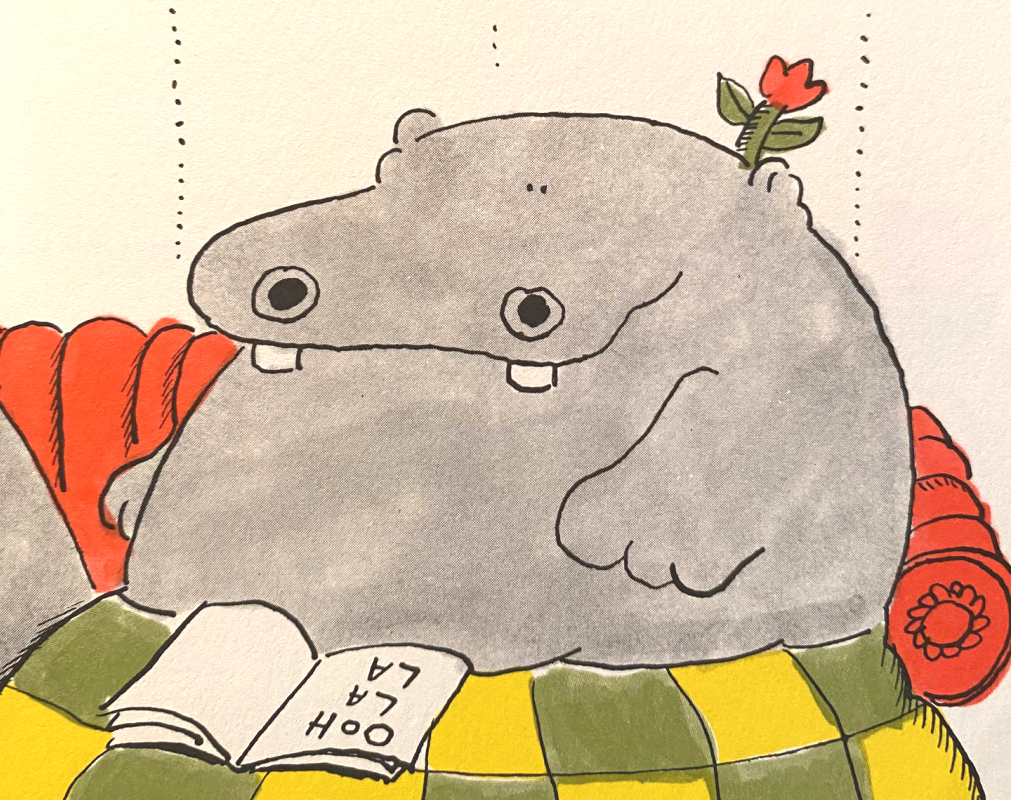

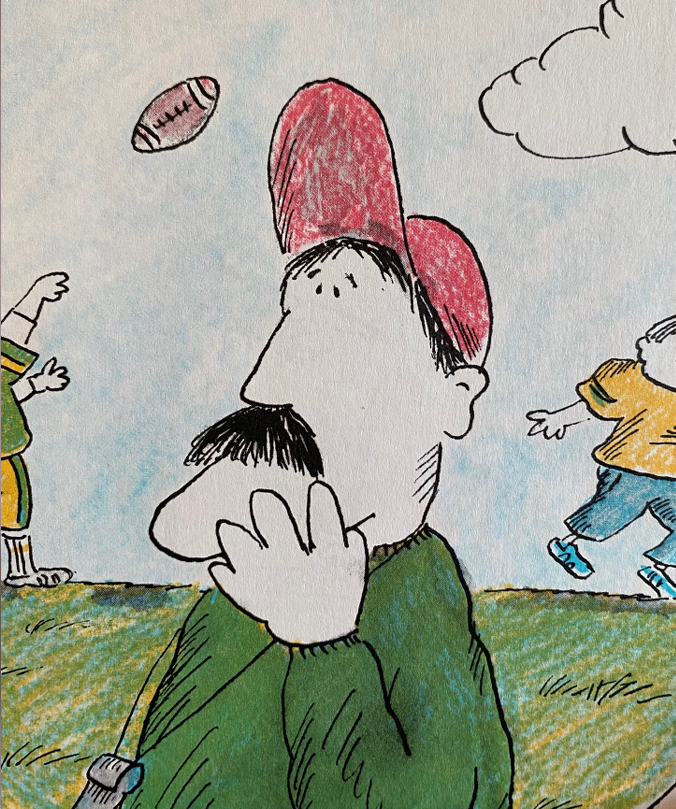

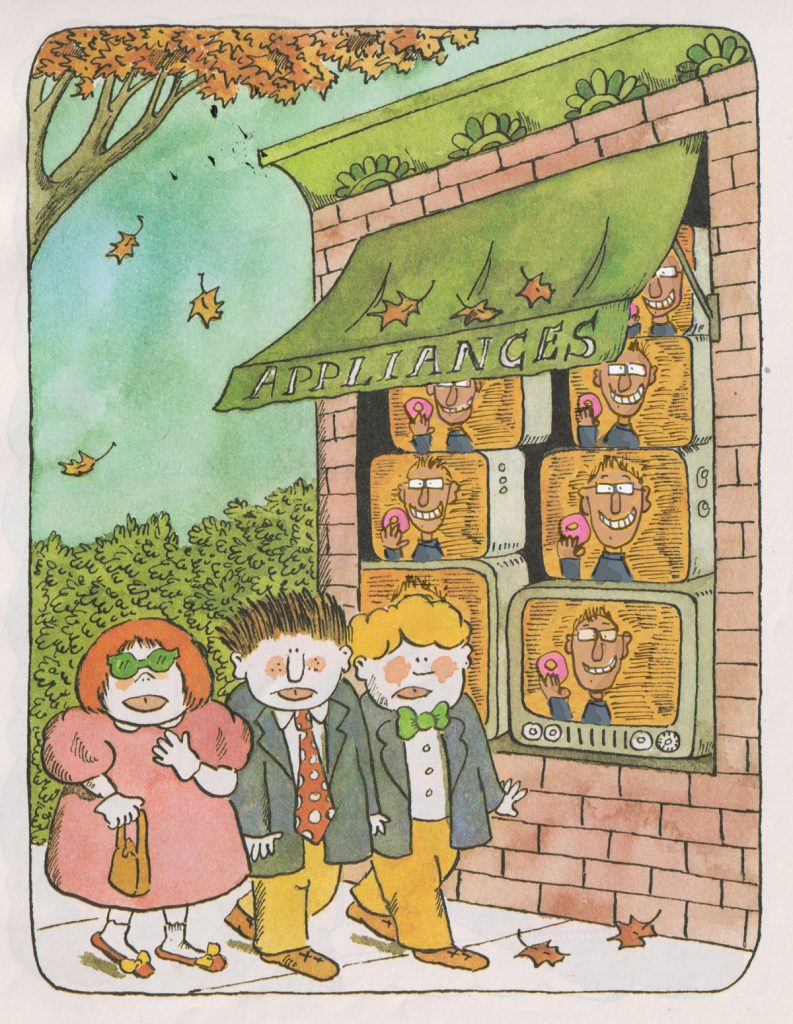

There’s a character that appears in many of James Marshall’s books. It’s this guy here:

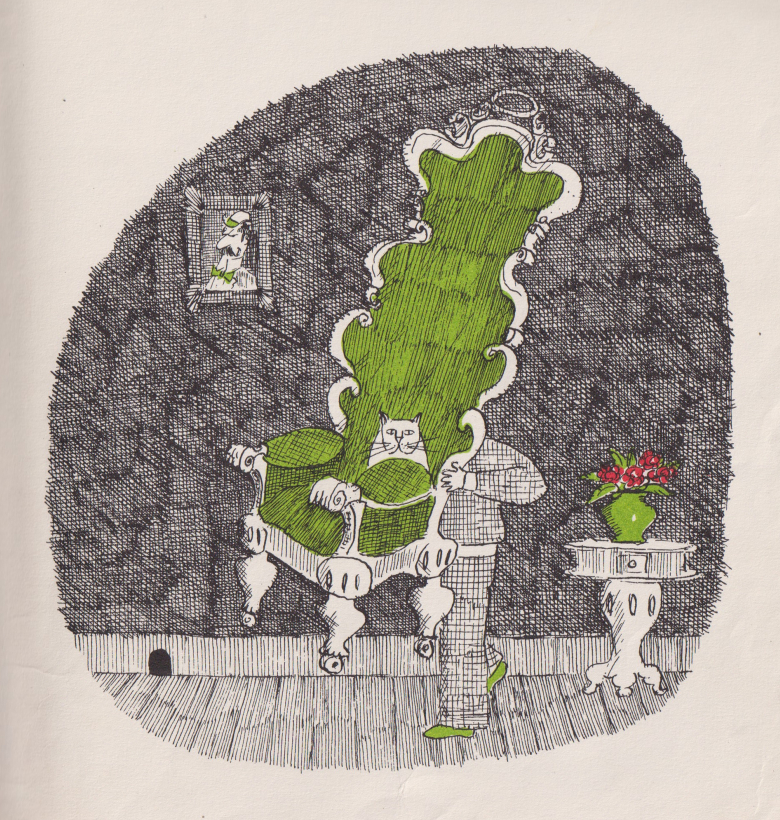

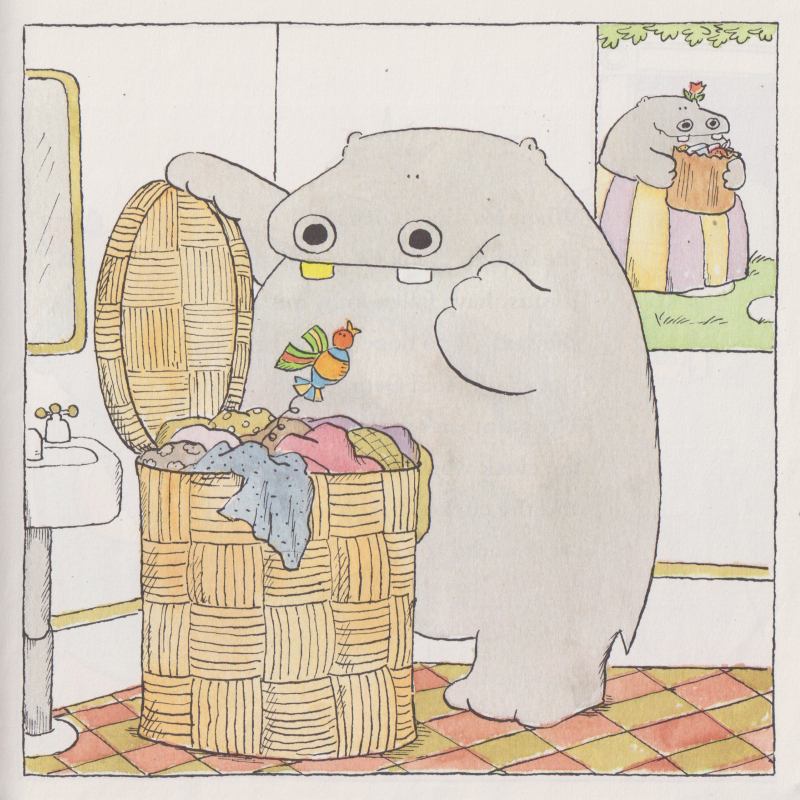

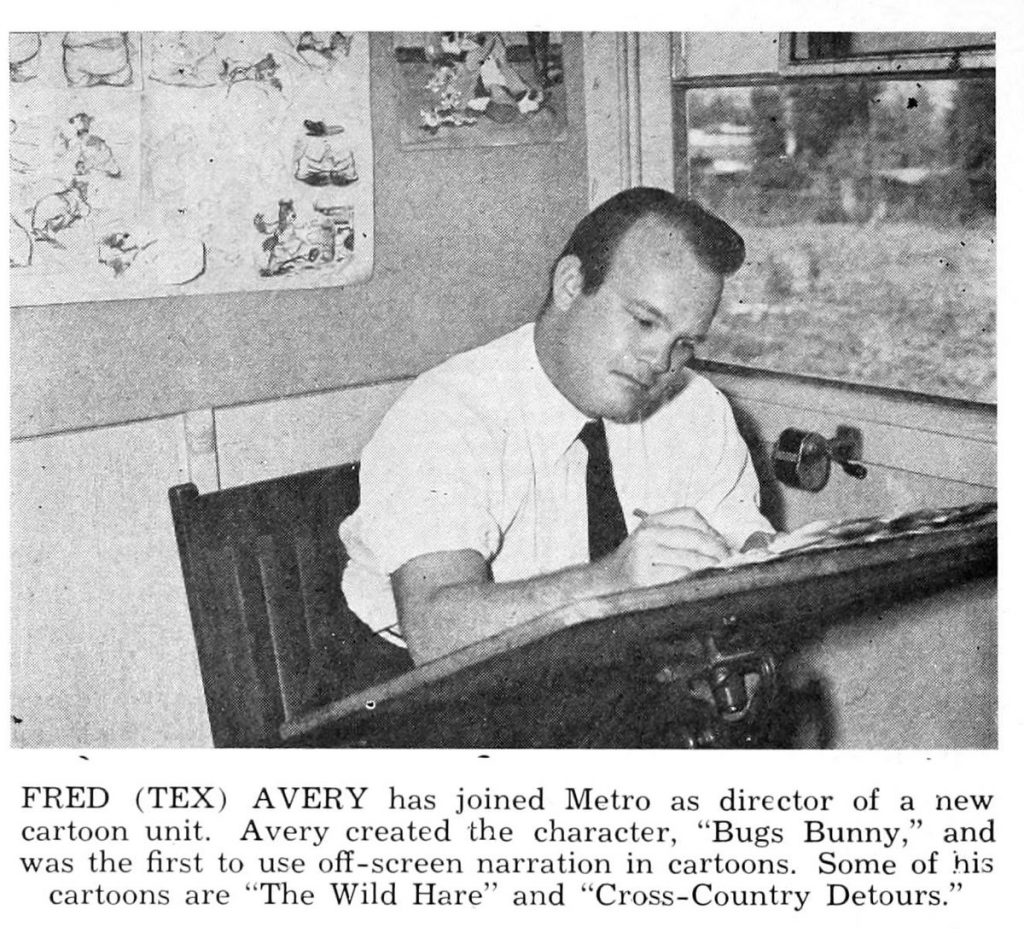

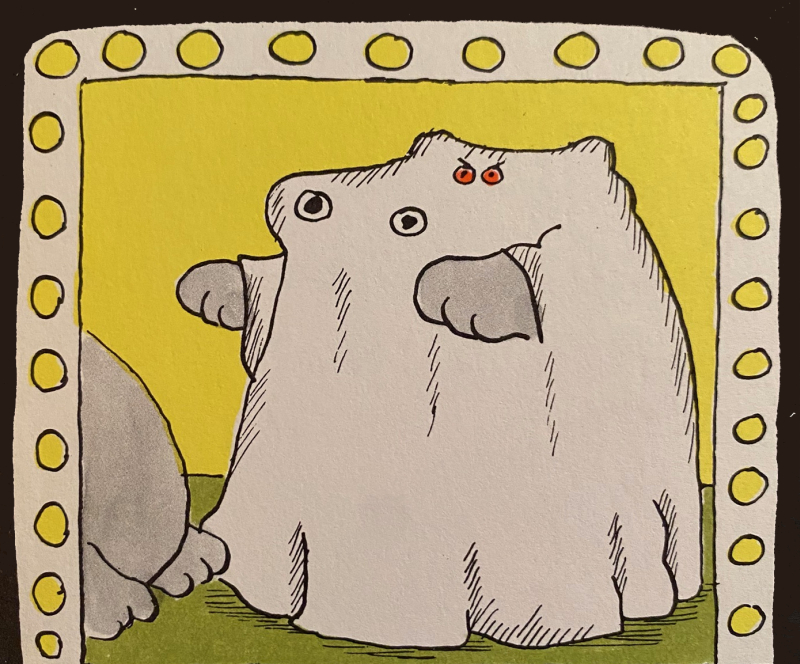

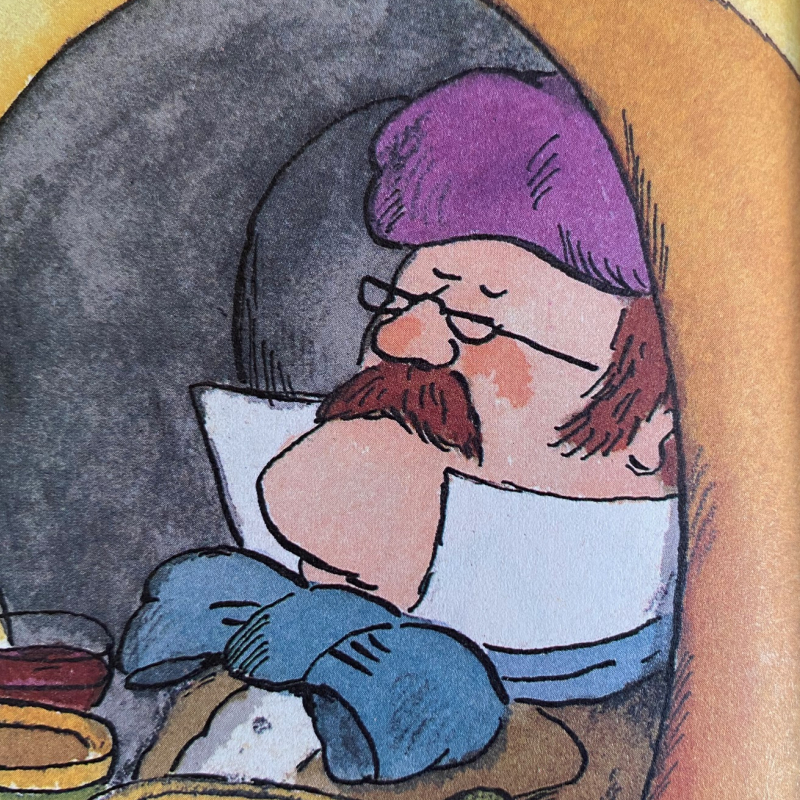

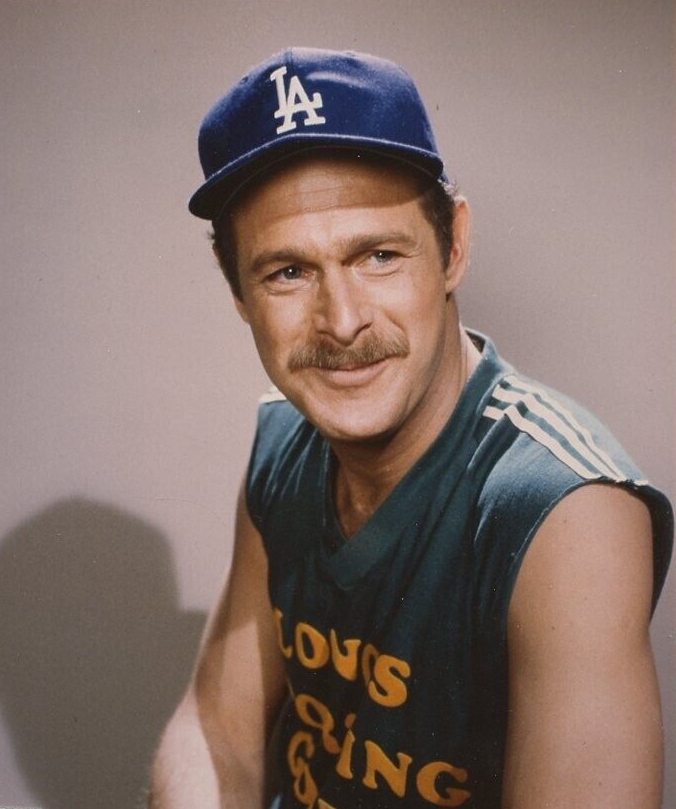

He appears often enough that I’ve always figured it must be a self-insert, a caricature of James Marshall himself. Never having seen an author photo, I decided that James Marshall must have looked like television actor, Gerald “Major Dad” McRaney (I’m a child of the eighties and I watched a *lot* of TV). It made sense to me because if this:

equaled this:

Then it stood to reason that this:

Would equal this:

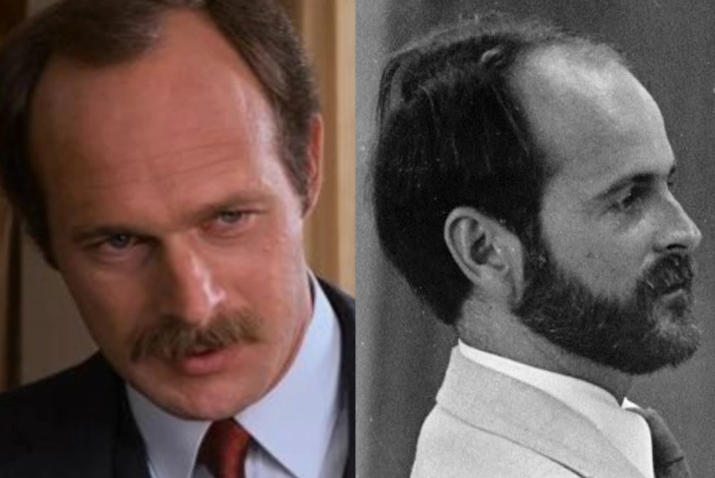

Many years later I would see my first photograph of James Marshall (again, on the Wandervogel blog) and I realized I wasn’t far off.

The Inexplicable Inquiry: How did I know???

*****

*****

STORY NUMBER THREE: THE TIME-TRAVELLING DONUT SALESMAN

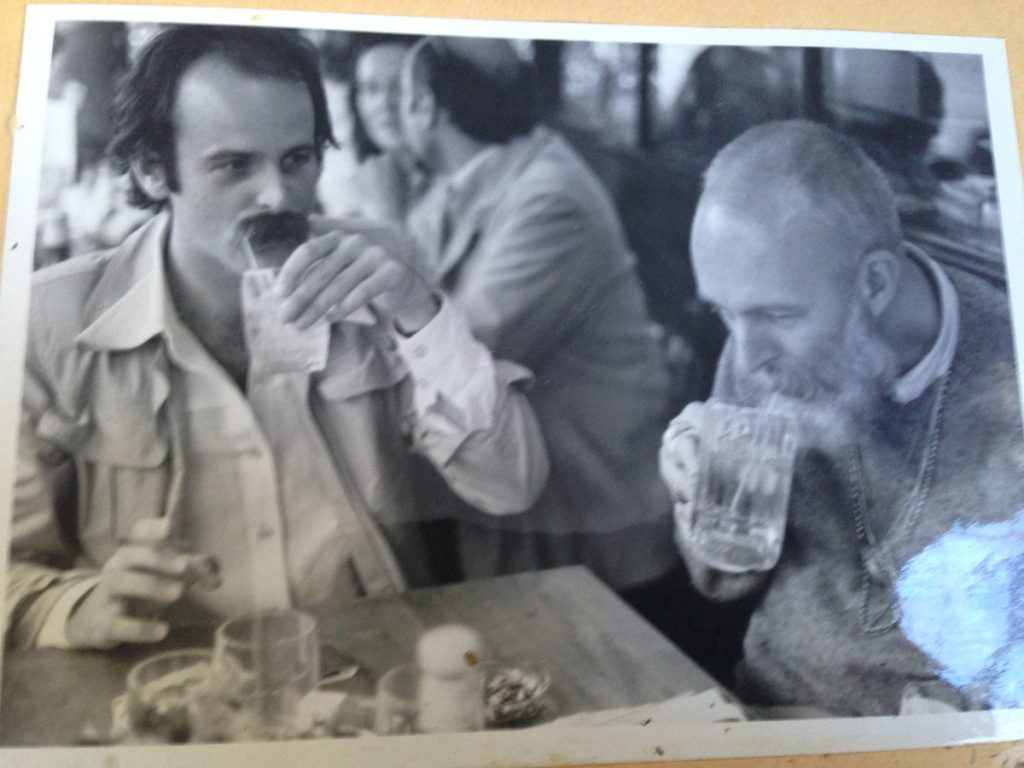

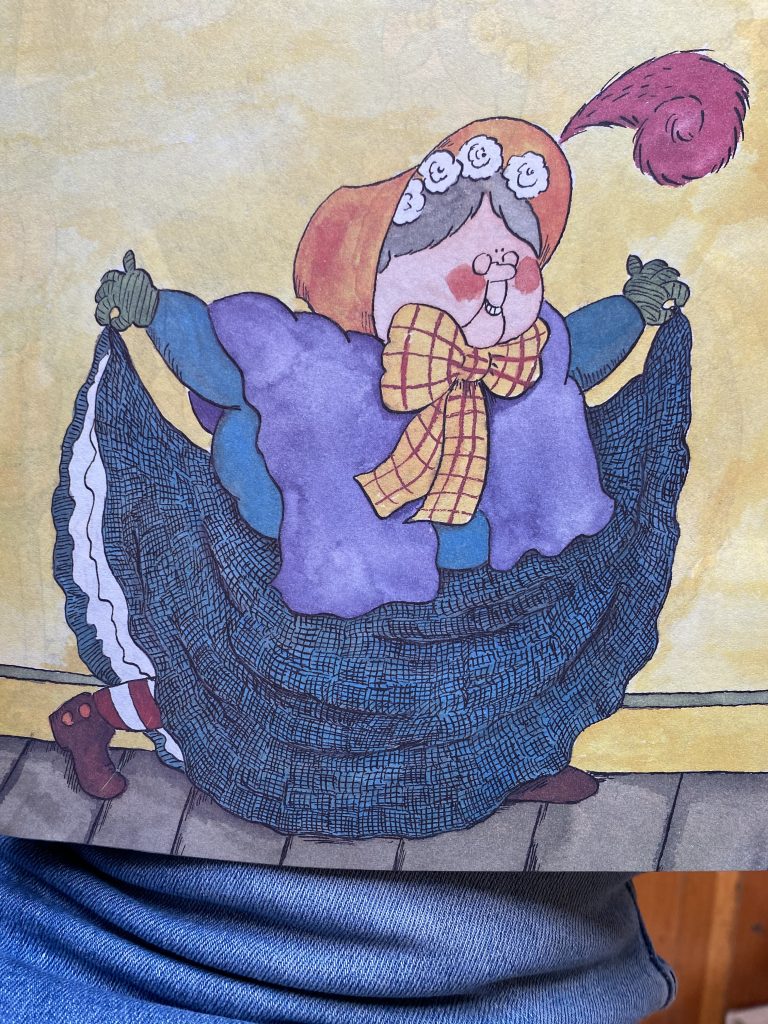

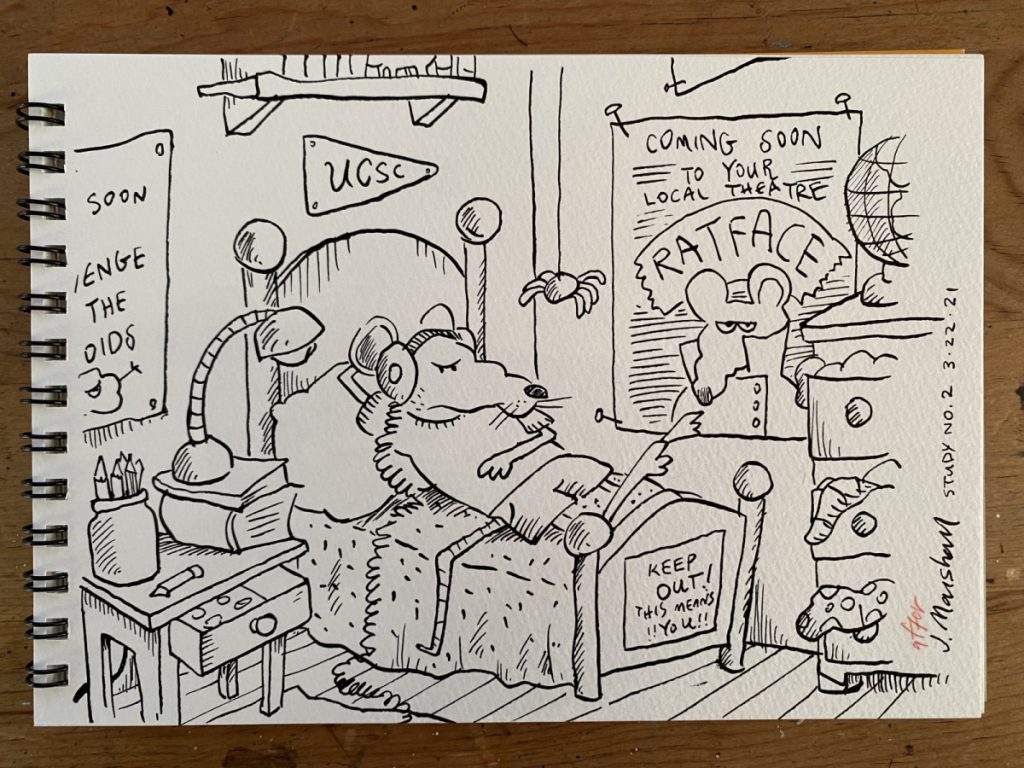

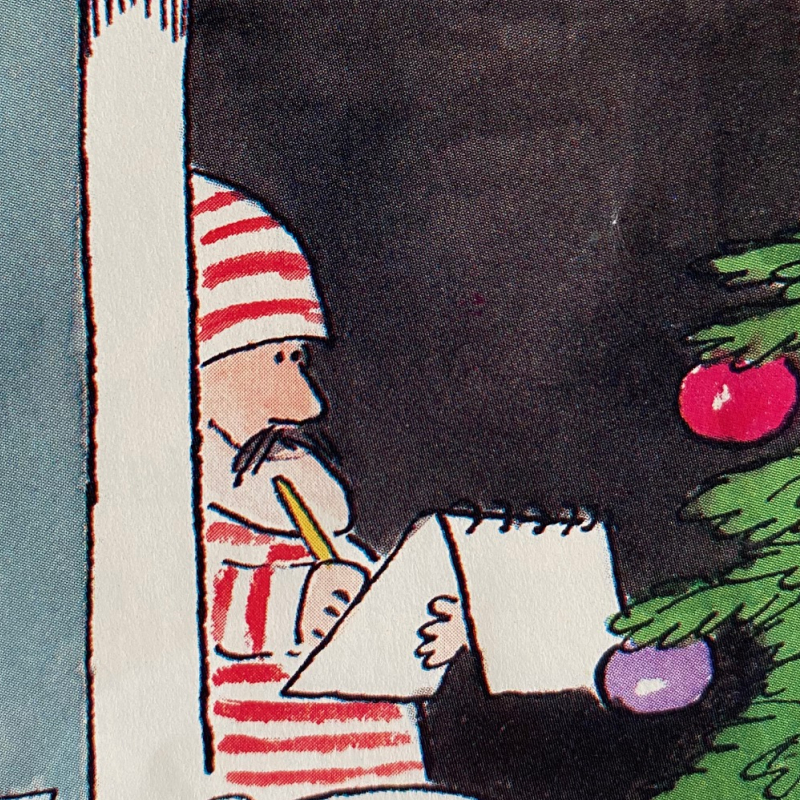

Speaking of uncanny resemblances… look carefully at the televisions in the appliance store window.

The Confounding Conundrum: WHAT AM I DOING IN CRAZY TIMES AT DANCE CLASS????

*****

*****

Okay, so probably only one of those stories is a mystery. Story 2 could be a result of Marshall and I sharing a certain visual literacy, Story 3 is a straight up con (CONfounding CONundrum, indeed) but Story 1… I dunno. It could be intuition. It most likely was. But on the eve of Spooky Season I always wonder if it was something more.