Appreciation: Towed by Toad

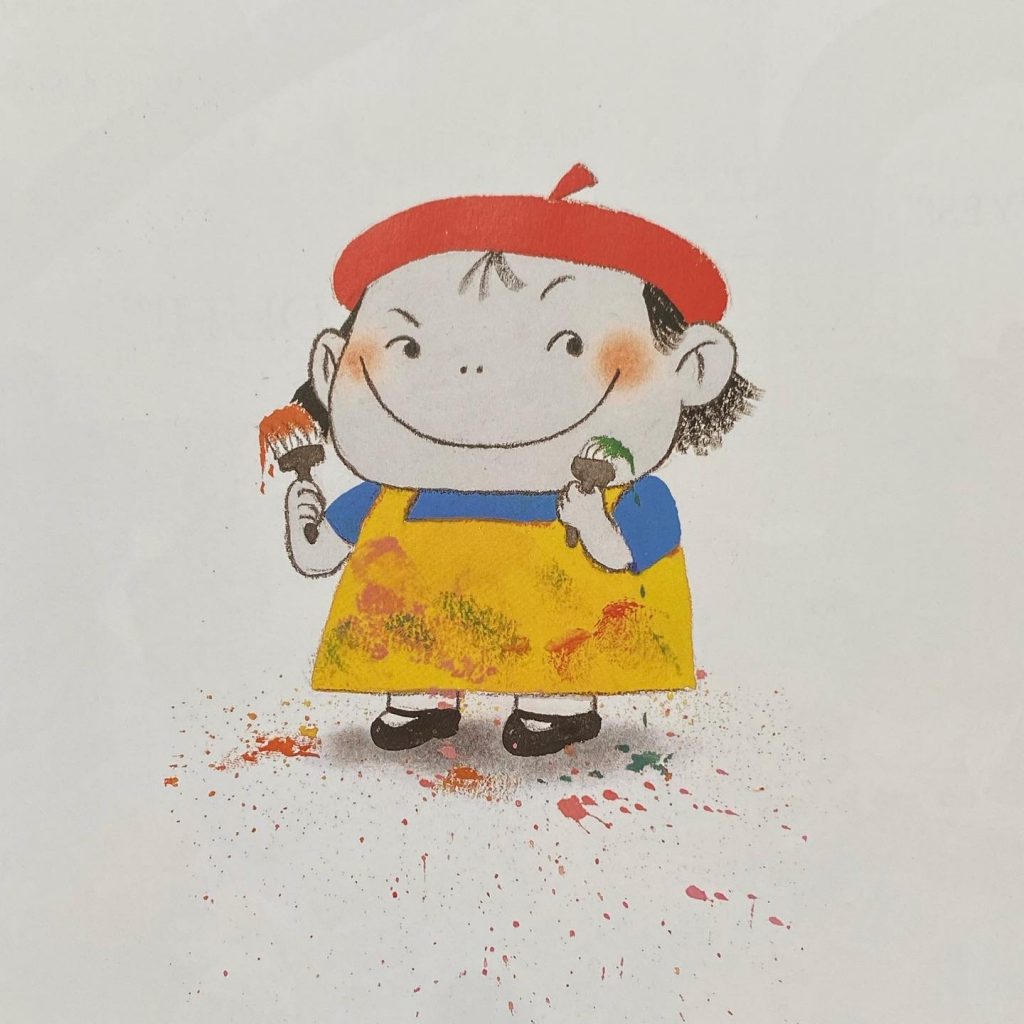

Yesterday was the American Library Association Youth Media Awards and, as happens every year, there was a stunning display of beautiful and important works by talented and intelligent human artists presented by enormously dedicated book people culminating in a celebration of those books deemed most significant, BUT, if I may, I’m going to talk about me for a minute.

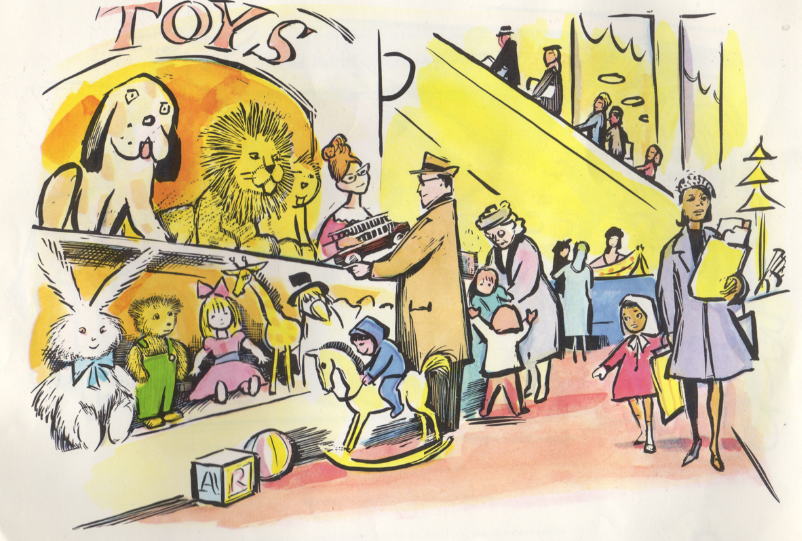

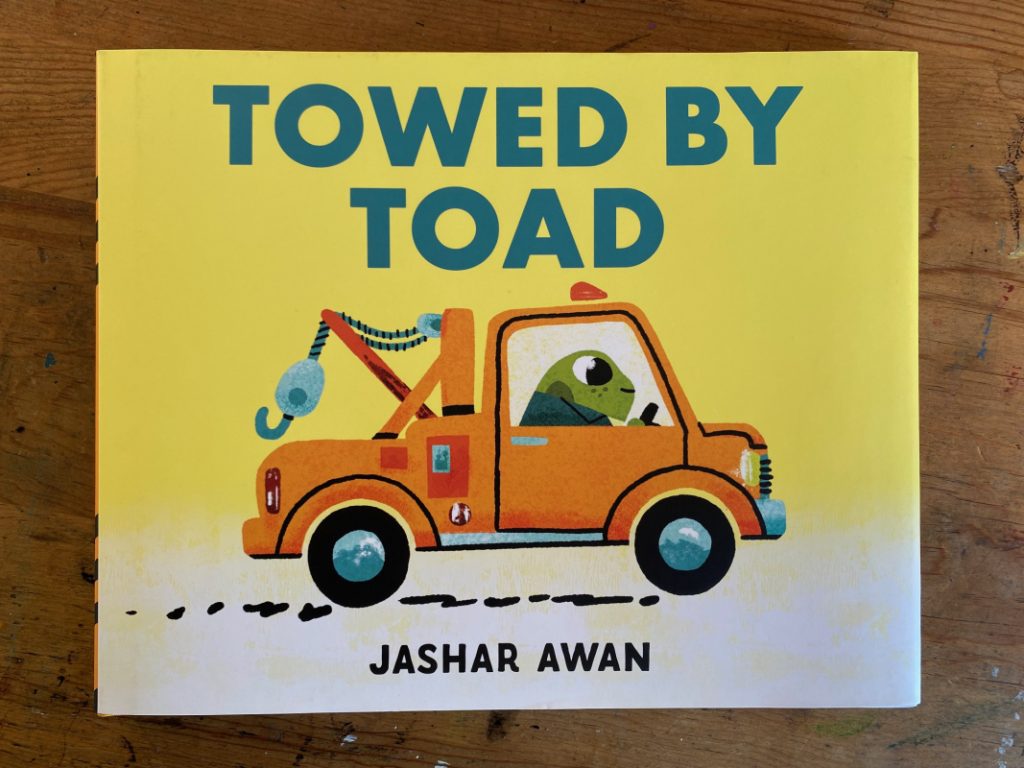

SO THERE I WAS, at my desk, the ALAYMA livestream playing on my phone, wondering what I was going to blog about. Suddenly it was time for the Geisel Award, the prize given to the “author(s) and illustrator(s) of the most distinguished book for beginning readers published in English in the United States during the preceding year.” It’s the award for what’s commonly called “beginner books” (think Cat in the Hat), but somehow I always (erroneously) equated it to a humor award. I was wondering if maybe there should be a humor award and if it should be called “The Jim” and then suddenly I heard the announcer say “and the award goes to TOWED BY TOAD”.

I felt an immediate, intense thrill. This was a surprise to me, I’m active on social media in #kidlit circles (less and less as it gets harder and harder these days) and have gotten to know a lot of talented, intelligent, human artists but I’m more likely to call these people (wonderful as they are!) “fellow authors” or “kids book colleagues” than I am “friend” (parasocial relationships etc etc). Still, I doubt I’d have been any happier if I was in person at a banquet celebrating Jashar’s win. What I can say with certainty is that I really admire Jashar and I really, really like TOWED BY TOAD.

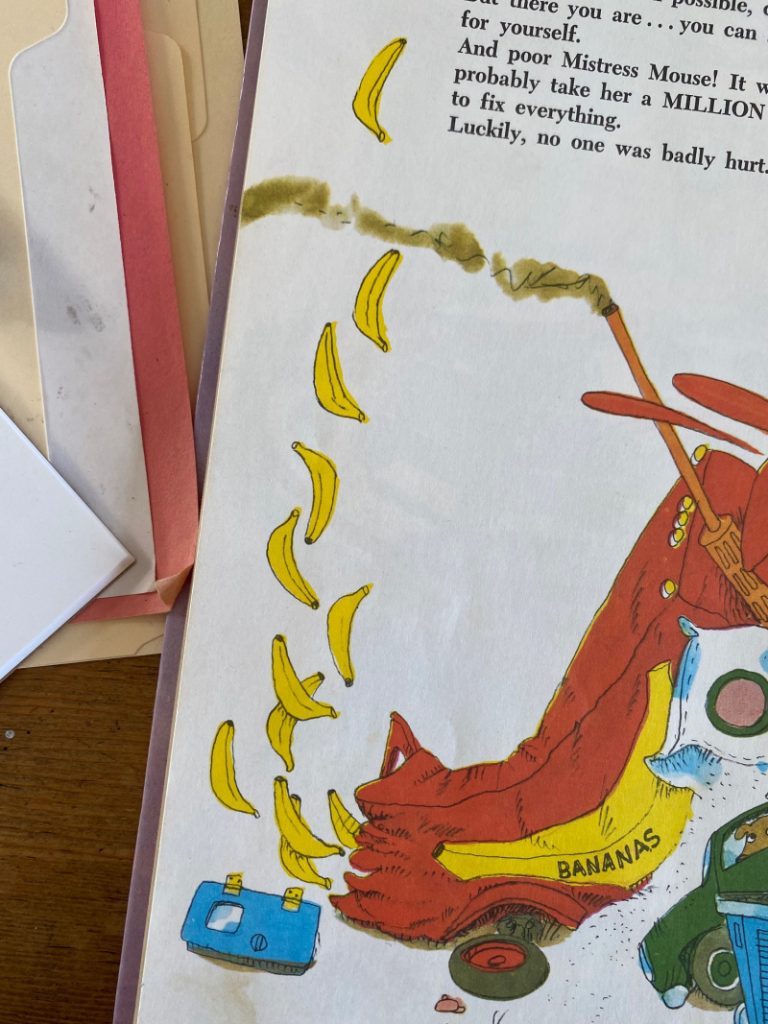

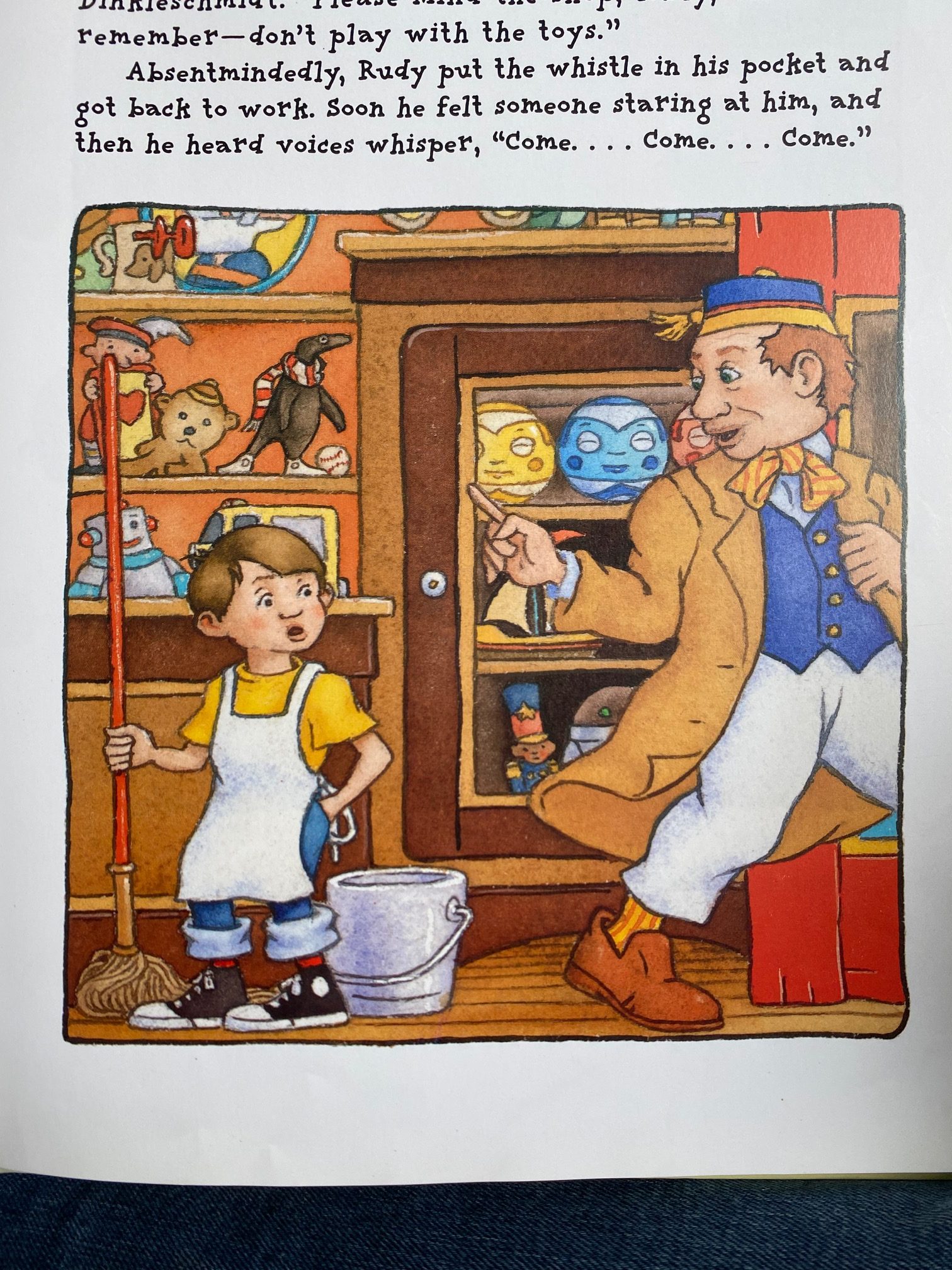

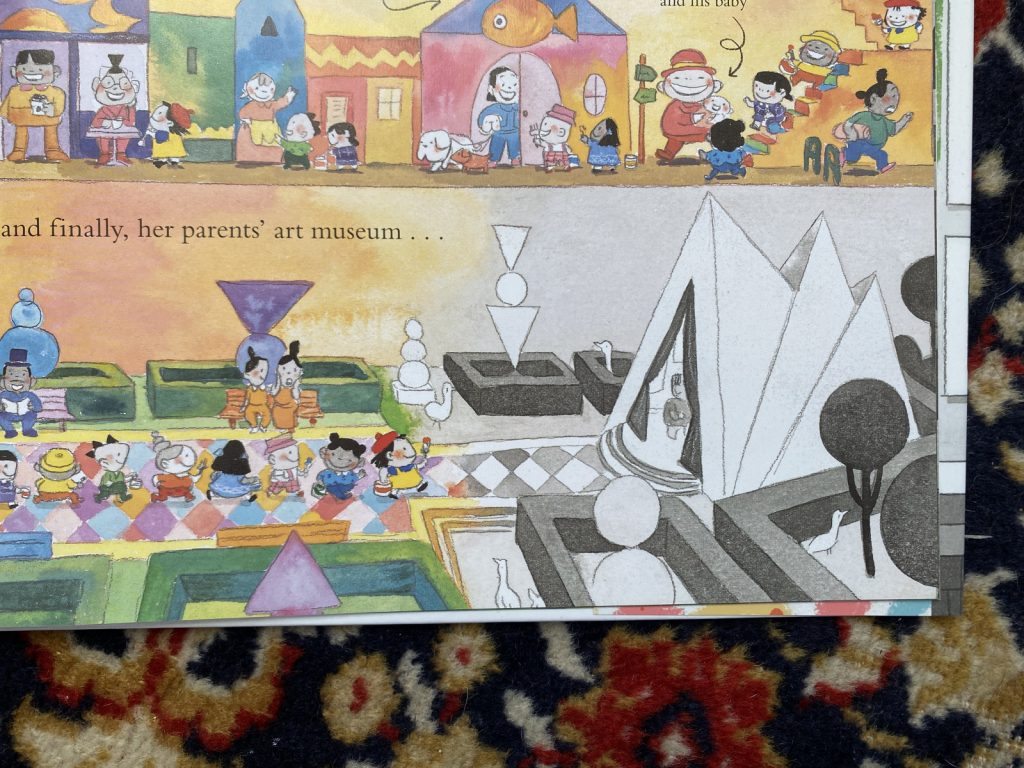

I had, actually, meant to throw out an appreciation for this book for a while, so here we are! Let’s dive in. First, the endpapers:

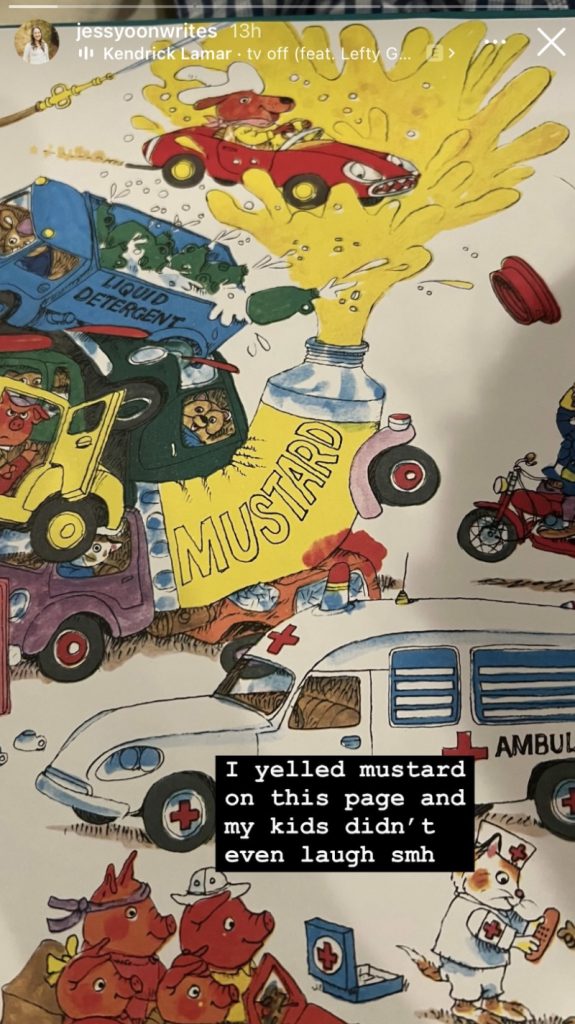

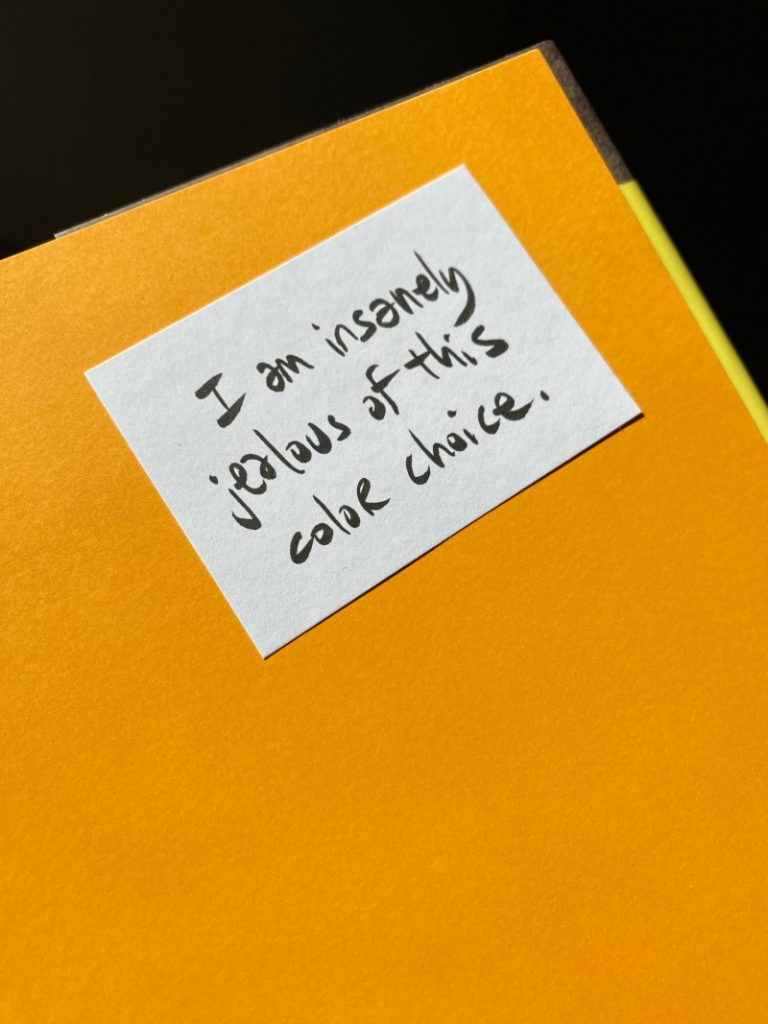

Of the seven elements of art (line, shape, form, color, space, texture, and value), Jashar’s ability to draft appealing shapes impresses me to no end, but TOAD really has me thinking about how well Jashar handles color. It’s so good. That yellow on the endpaper is just perfect.

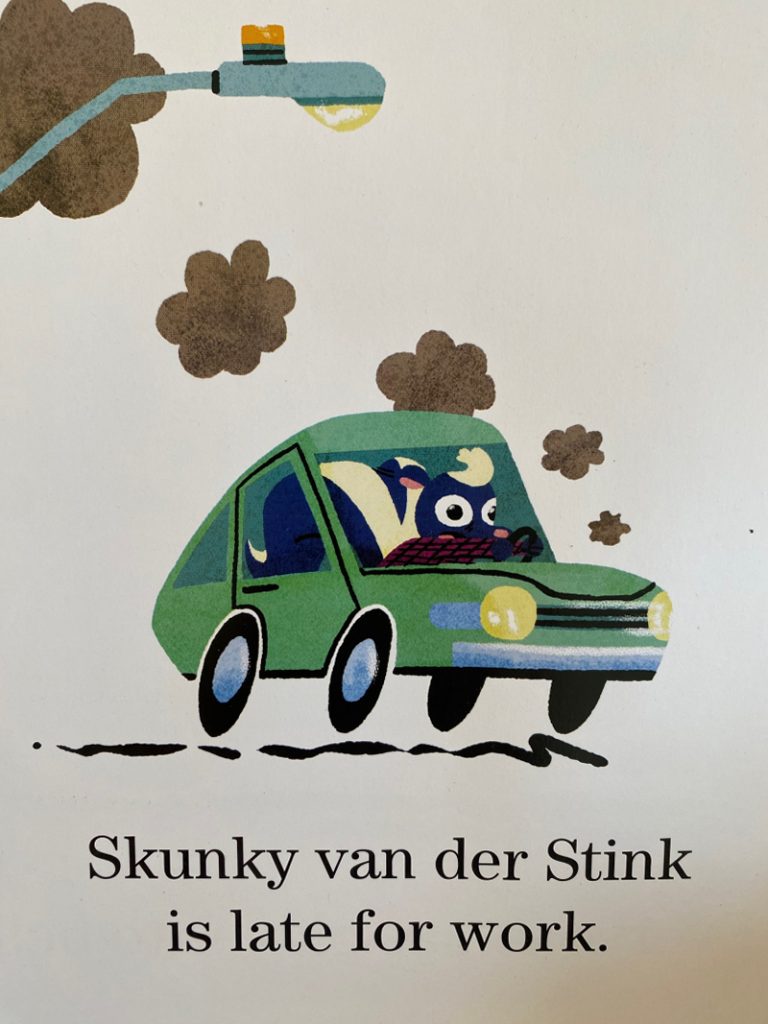

Another perfect thing, the skunk’s face on this next page. Also, the skunk’s name.

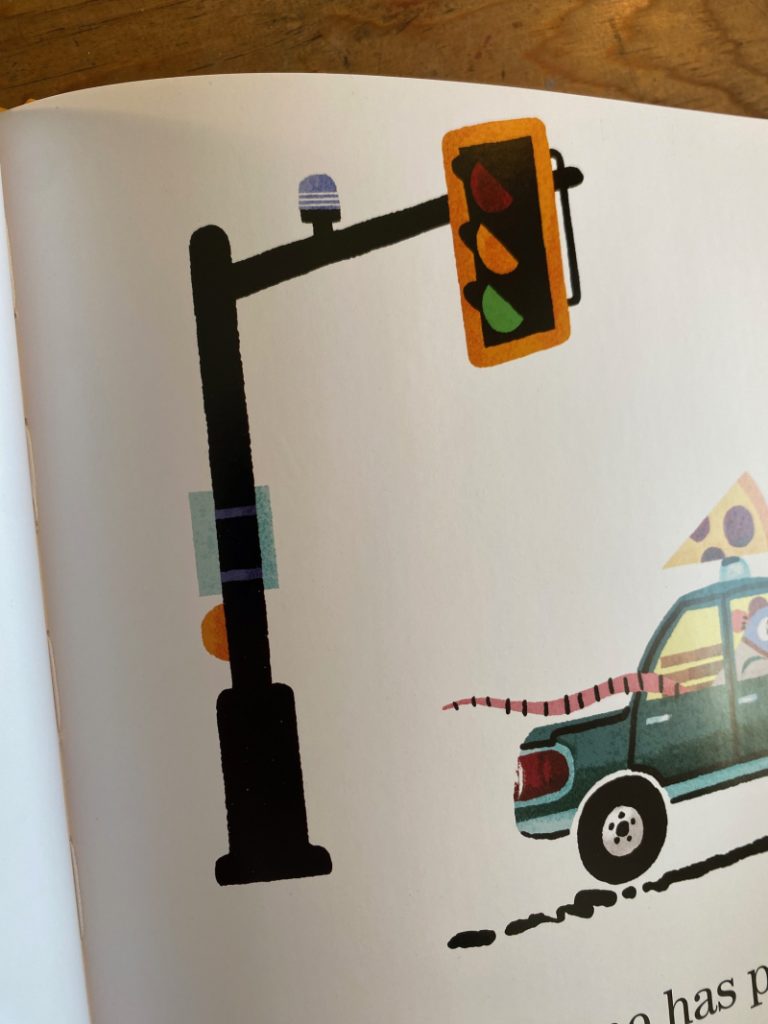

There are also these small details in the book that are integrated so seamlessly into the illustrations. Like the transponder on this traffic light. It’s extra, but not superfluous. Does that make sense? I don’t know, I just really admire it.

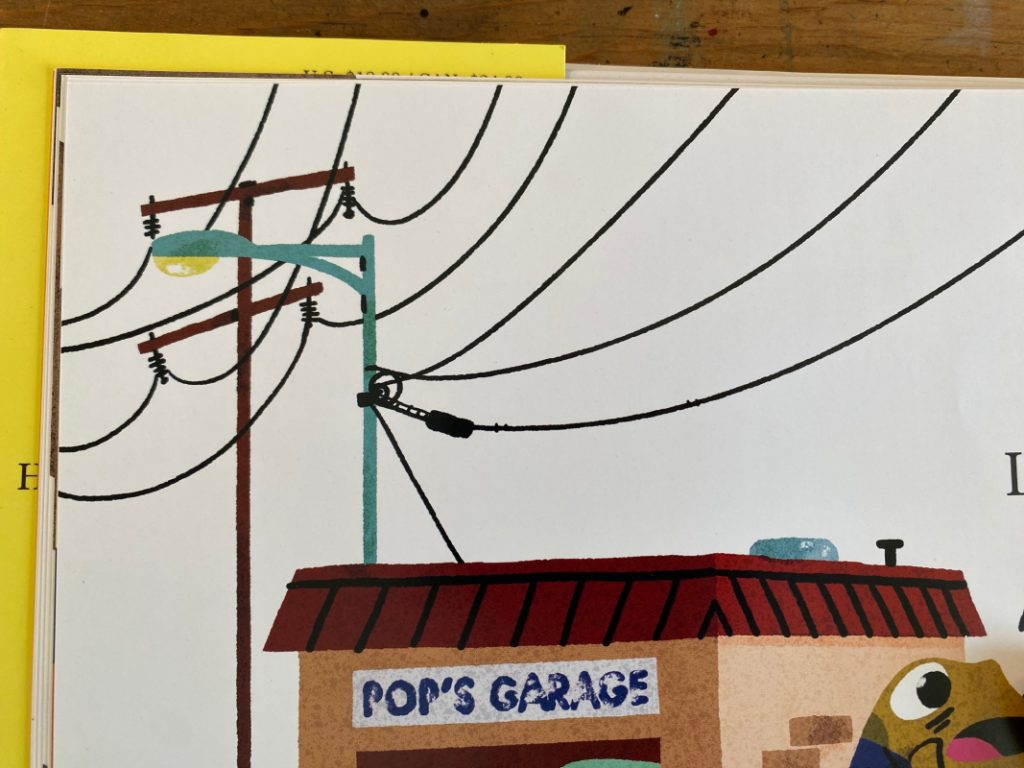

I also admire this part with the powerlines above Toad’s repair shop. It’s a cacophony of cables but it reads so well.

And it’s not all style over substance. The part I might most admire in TOAD is this little detail at the beginning of the book. This little fly in the frying pan. I love how this open up a space for the reader to imagine what Toad has for breakfast. What do you serve with fried flies? Weevil waffles? Grapefruitfly?

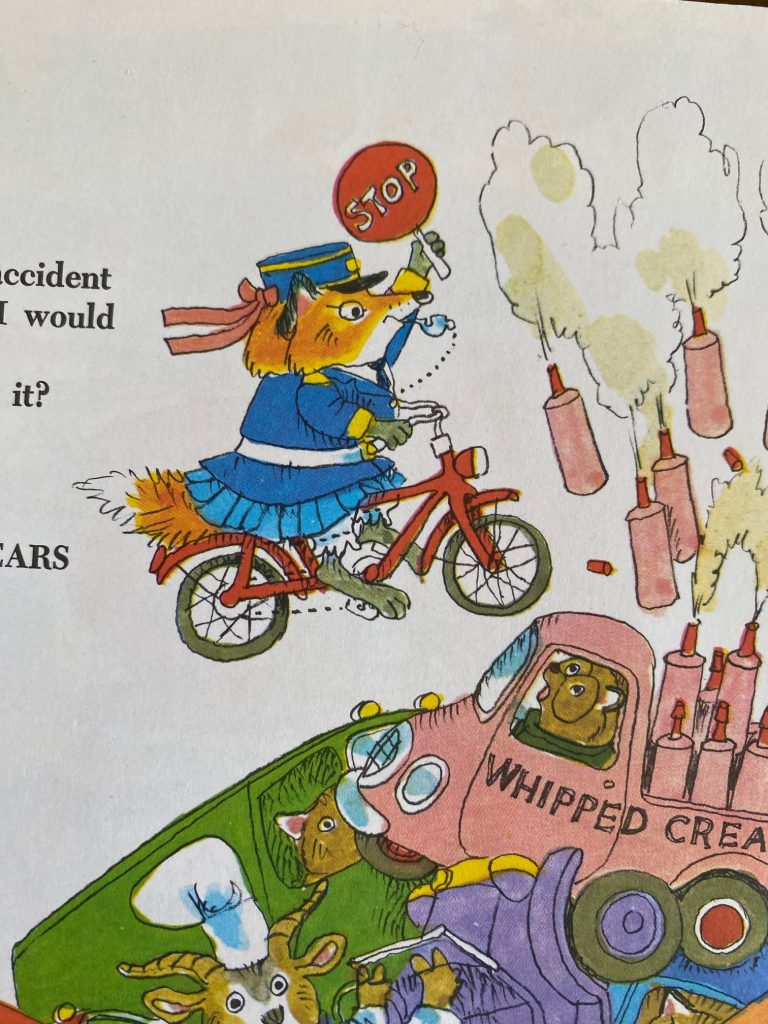

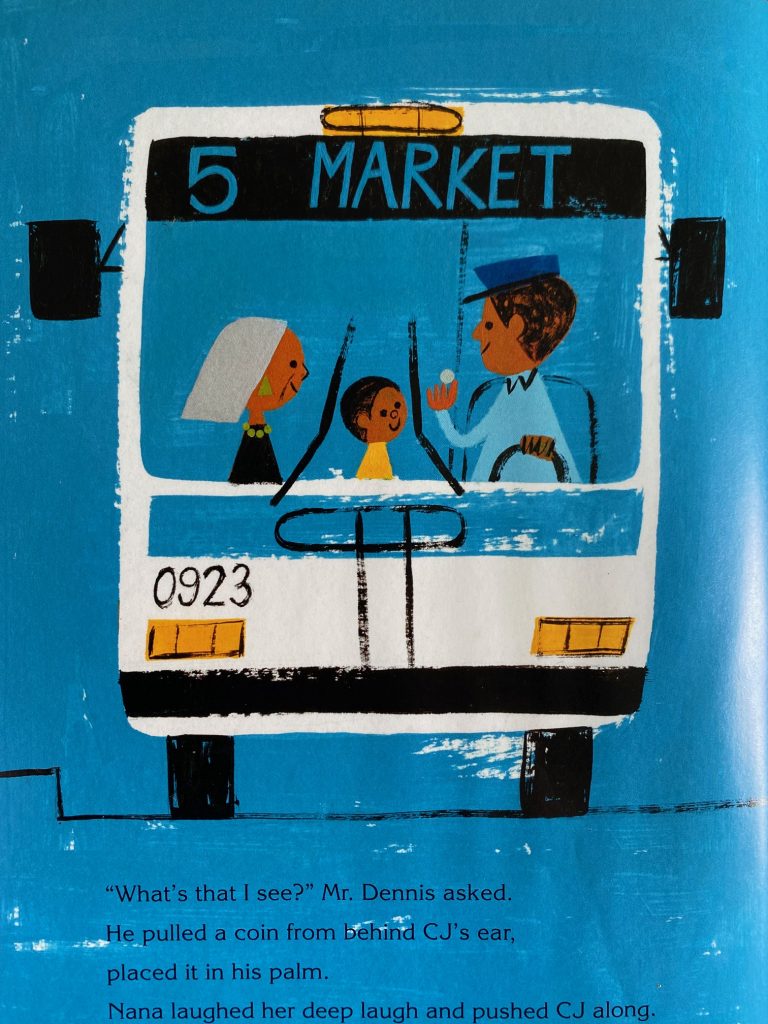

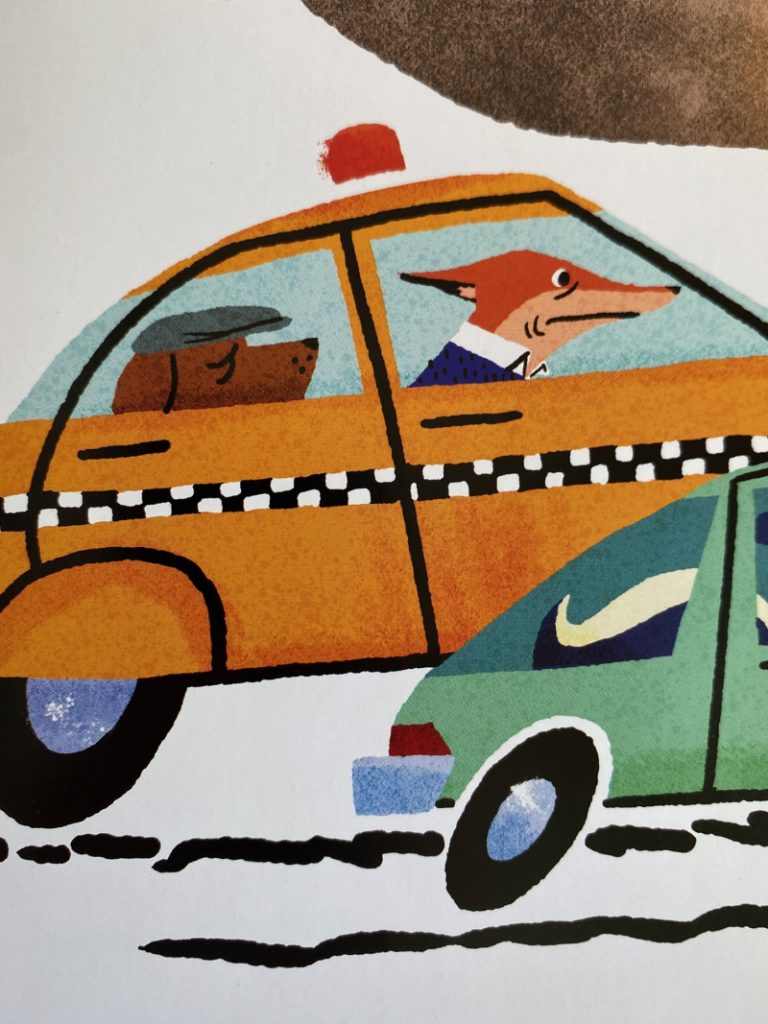

Similarly, the various motorists all have stories you can imagine. The one I’m most intrigued by? The taxi cab duo. Behold:

If you ask me, the dog in the back seat looks more the “cabbie” type. He’s even got the cap. PLUS, he looks like he came out of GO, DOG, GO! So why is he in the backseat? The fox, meanwhile, looks like the male lead in a romantic comedy who is on his way to the airport to catch his lady love before she boards the plane for Tuscany but he’s hopelessly late. I could be taking this fiction too far, but the pictures do compel reading.

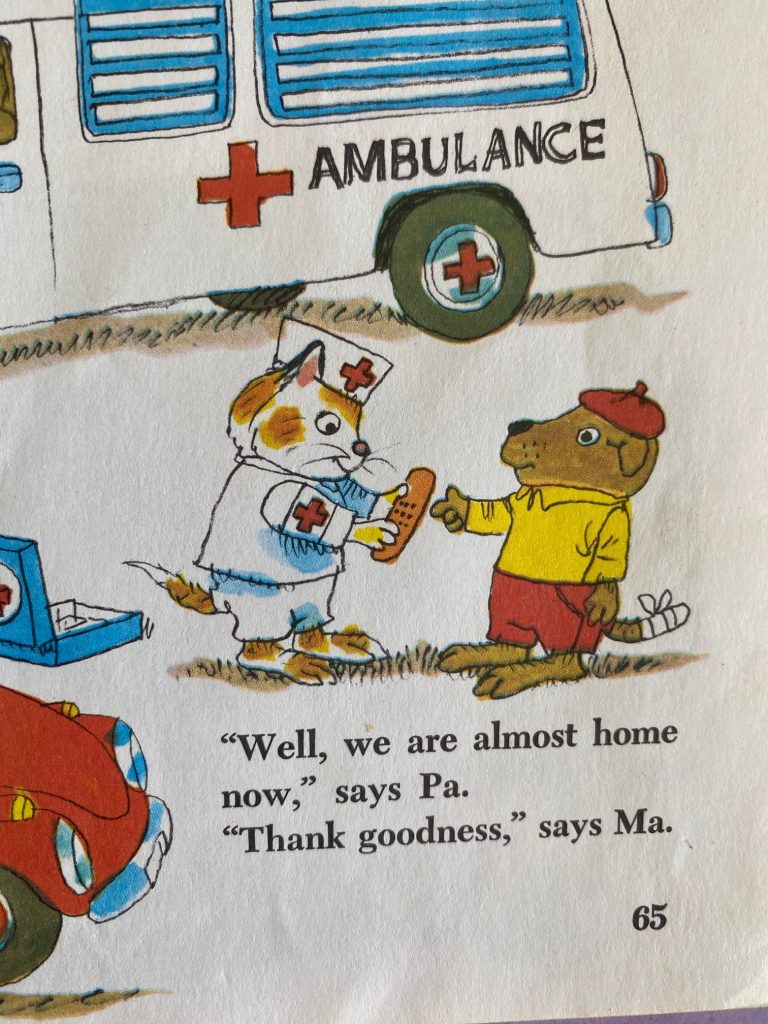

And speaking of reading, the text is friendly, inviting, reads as clearly as the pictures and carries a real sweet message. It’s honestly such a good book and I’m very happy it got recognized today.

Appreciation: Towed by Toad Read More »